Residency Reflections

By Arturo Desimone

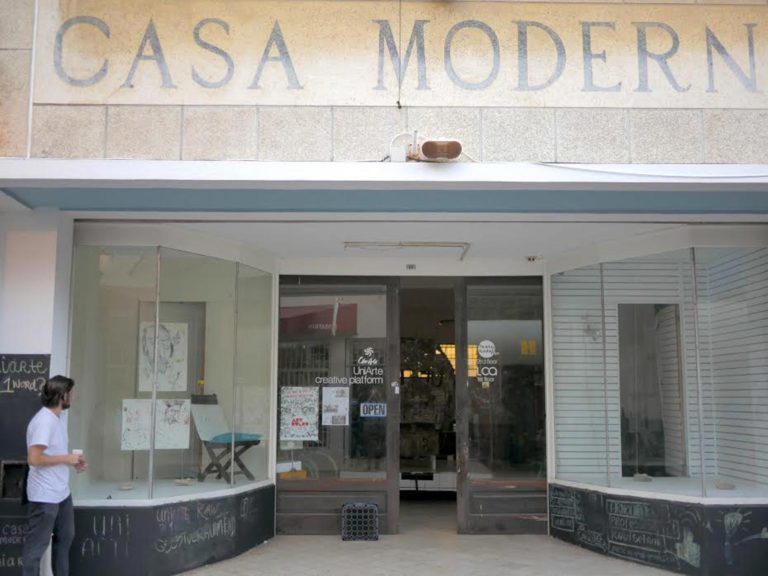

The opportunity to reside for a month at Uniarte, where I worked in the old Casa Moderna edifice while staying in the historic San Marco hotel, brought me into regular and fruitful contact with the arts and literary scenes of the island which appear more vibrant and lively than expected. The building of Casa Moderna and its interiors are an important relic (or reliquary) from a period in the history of the Caribbean, with antique machinery and objects, and a backdoor that opens to the old Havana-yellow walls of the oldest synagogue in the Americas, the Sephardi synagogue in Punda.

It was impossible not to write a poem in these surroundings.

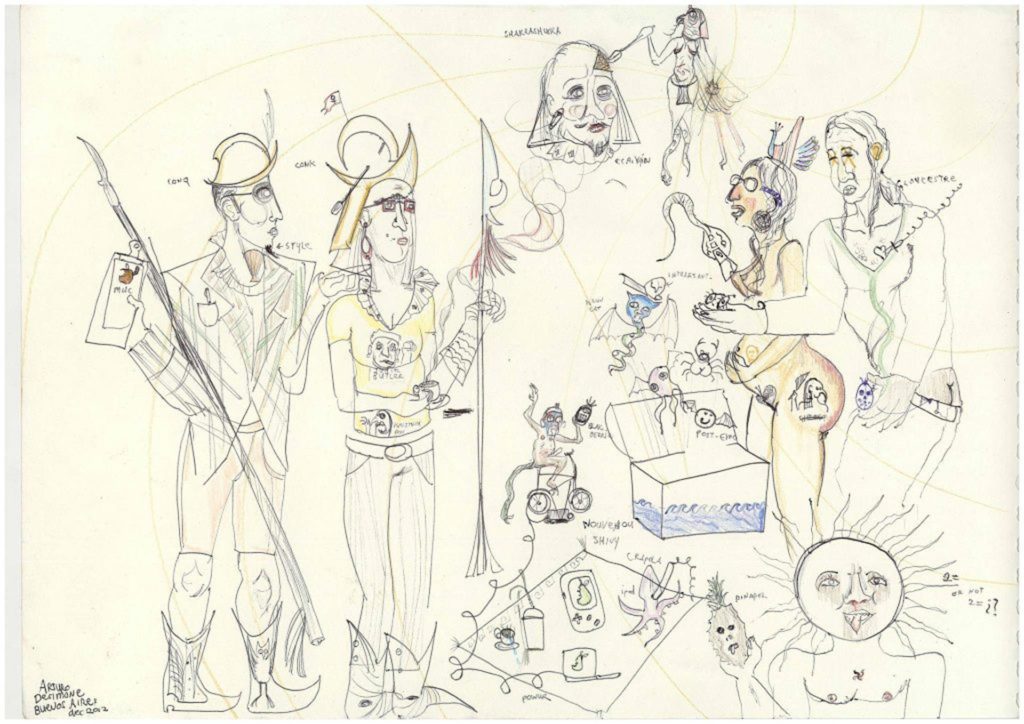

During the month of February when I was traveling in Cuba in relation to an art and literature festival, I had begun a series of drawings with African themes that began to confront me as I noticed more of the African cultural and religious influences upon daily creole society in Cuba, internalized by nearly all factions of the Cuban population and inescapable at any hour whether nocturnal or sunlit. I began to produce a series of African-themed drawings. I thought I would continue to emphasize those themes during the residency to come in Curacao. To my surprise, once I arrived in Curacao and could see the steeple of the Sephardic monument from the sealed windows of the San Marco hotel, and while spending time in Punda and in Otrobanda, I began to delve more into another side of Caribbean culture, that of the displaced Judeo-Spanish population which settled Curacao, as well as other parts of the Caribbean and South America. I visited the museum of the “Snoa” where very old and elaborate gravestones of 17th century Iberian Jewish merchants are preserved and on display. I drew, copying the friezes and their inscriptions in Ladino or in Portuguese. These mysterious stone friezes and reliefs contained fables and a fabulous humor and an awareness of death, mortality and political instability of the times.

I took a van to the Blenheim cemetery. I walked a long time amid the old 17th century graves. Many of these precious tombstones are eroded and faded by the refinery’s gases, a great pity as these are important artefact of history and works of art.

My host Avantia Damberg, (one of the curators of Uniarte) is fantastic and was incredibly engaged and helpful in promoting my work and introducing me to the art-scene and art-world and literary circuit of Curacao. I met caretakers of the Mongui Maduro library, and at the Kas di Kultura saw a book presentation by exuberant poetess and performing artist Crisen Schorea who presented her book in Papiamentu, Sinti mi Sintí; a literary evening of the local grand-master of bohemian ceremonies Roland Colastica (who I knew before having met Avantia) in a tamarind garden; I met a local visual artist and poet Ashley Mauricia who showed us how he lives in a haunting former dungeon for slaves within the old fort of the bay of Willemstad (a residency which influences and shapes his poetry and perceptions) Avantia brought me to the talk-show CBA-New Day to be interviewed in Papiamentu (though I speak more Papiamento!) by the elegant talk-show hostess, Meritza Haakmat (who is also a singer of Caribbean and Latin music) and read my poems in Spanish on national television. This is an important step and experience.

On an island like Cuba, and perhaps on some other Caribbean islands during other periods of history (Martinique when Aimé Césaire was in politics, for example) it was more common to have poets reciting on television, and prices of books were accessible for a more general audience. I hope the wider Caribbean, and especially islands like Curacao and Aruba can also attain that kind of cultural engagement, and reading on television (regardless of the extent of an audience for poetry watching the live show) was a way of stepping out of the safe realm of ideal contemplations and opinions, into the more uncertain and unknown sphere of beginning and of enactment.

While at the residency, we planned a series of lectures and workshops. One of these workshops would be an introduction to literary translation, in theory and practice, for people on Curacao of all ages. I find this subject to be very important, because while delving in the National Library of Curacao it was nearly impossible to find many of the important 20th century writers of the other Caribbean islands: not one work by Martiniquean poets like Amée Cesaire, no St-John Perse (Guadeloupe) no Jaques Roumain or Marie Veux-Chavet (Haitian literature) no Luis Palés-Matos (one of the great poets of Puerto Rico of the early 20th century) only two books by Derek Walcott in the permanent collection, none by Cuban poets except for a Dutch translation by Cees Notenboom of Nicolás Guillén (without the Spanish original text—very unfortunate on an island where people can read and understand Spanish) and nothing by José Lezama-Lima (also of Cuba.) An employee at the Biblioteka Nashonal Frank Martinus Arion explained that many of the titles once formed part of the collection, but were ‘’cleaned out’’ to renew the catalogue years back. This seemed a very alarming situation. During my time on Curacao I met poets who actively promote education in Papiamentu, and believe in the importance of literary translation.

I prefer to give a more unconventional type of writing workshop than the typical creative writing exercise, and as translation seems of preeminent importance (this is I also argue in my essay ‘’The Divided Dutch Antillean Writer’’ published in the Caribbean journal SX Salon) I planned a workshop in which I would give “theory of translation” referring to many present-day translators from the world over, quoted on how they go about the ancient task as old as the Rosetta stone. Ideally, I wanted to arrange for old typewriters for the workshop participants, but since these were hard to find on the island, I thought having people work by hand, tailoring upon colored paper like the medieval monks, would suffice.

Unfortunately, due to the tumults of the elections season as well as King’s Day festivities, few people signed up. This was, however, not only an unhappy surprise. We had expected that on Curacao it would be difficult to find many eager participants in literary workshops, especially by a foreign writer who does not mobilize a large network of his own, unlike the local poets Schorea and Colastica. More importantly, is that I was able to view Curacao at the very crossroads of a political eclipse after the island was in a period of uncertainty due to party politics. To see the celebration of King’s Day festivities take place just before the election day on a self-governing island, was surreal. Observing societies on the brink of political change and tension is integral to my writing. My drawings are also often a view of political landscapes of injustice, as I am often drawing fables of those who live in the street or on the edge of the street—only because these were my most visible surroundings for a long period.

The more successful lecture concerned the subject of an Argentinean poet, Juan Gelman, who wrote one of his books in the Sephardic language (Judezmo, or Ladino) during his exile. The first talk about Gelman was improvised, before an audience of German students of Romance languages guided by Curacaoan linguist and educator Ini Statia, at the Mongui Maduro museum. I had a very interested audience at the Casa Moderna, and I emphasized the language of the poems during the lecture: the audience marvelled at uncanny similarities between some Ladino words and Papiamentu / Papiamento words, such as ‘’mundu’’ ‘’yabi’’ ‘’djaru’’ and others. Presenting Juan Gelman poems with drawings, and reciting both the original Ladino and my improvised Papiamentu spoken translations, led to an intertwining of two languages with very different grammars, yet possessing similar words. Both languages possess a rhythmic sweetness less easily detected in European languages. I used the theme of the Sephardic language while referring to the linguistic theories elaborated by none other than Frank Martinus Arion, the Curacaoan novelist and linguist, author of the linguistics study Kiss of Slave,( in which he wrote of Papiamentu’s origins in the encounter between the language of the West African slaves meeting the influence of Portuguese captors and Sephardic merchants, who were active in the tropics before the Dutch took over the international slave-trade from the Portuguese) Though it is dense material, my small audience consisted of Papiamentistas and enthusiastic promoters of Papiamento, already well-informed of all the linguistic studies and literary records of the language.

Avantia and Sharelly also introduced me to Nifa Ansano who hosts a daily online vlog, Pleno Punda, about political and cultural goings-on. I was very pleased to meet Nifa and the journalist assisting her, thereby gaining more insight into this fascinating island-nation that I was always somehow acquainted with, never entirely familiar nor foreign.

My major points of criticism or regret are only 3 in the otherwise splendid, energizing experience that I hope to somehow return to on the island. First, it was too short, only 1 month. In order to expand and elaborate a project that I had begun on the island, it would have been best to have two months (for example)

Second, because I depended on funding in order to consolidate my trip to Curacao, there was a lot of suspense waiting until the very last moment when our generous benefactors of the Prince Bernard Fund approved financing for the trip and residence: approval came in the day before the flight, and we lost the first booking while awaiting confirmation. I regret being in no position to fund residencies myself, being a full-time professional artist (literary and visual artist)

3rd is the fact that King’s Day celebrations at Uniarte/Casa Moderna involved an event in which young students from Instituto Buena Bista did performances and covered the outside and front of the Casa Moderna building with their writing in chalk advertising IBB. They did not clean up afterwards. The teachers and supervisors of IBB did not see any reason to talk to the students about the institute Uniarte and its foundation as a separate institute for the arts, nor did the teachers of IBB find it necessary to clarify that there is an exhibition by an artist in Casa Moderna. As a result, students moved about furniture and other equipment covering my drawing on the wall or leaning on the wall and left there writing on the sidewalk and outer walls just days before we had to do an official opening. It is unclear how Uniarte then benefits from such a generous predisposition towards IBB, while the latter regards it as a subsidiary or competitor with Roy Colastica and company

Though I am an Arubian artist who speaks Papiamento and I have the option of being based, if I wanted to, on the island neighboring Curacao, that in itself would not have made it easy to spend time on Curacao as the prices are generally high on these islands. It has an honor and very great pleasure, so thank you.

Arturo Desimone

1 Comment

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.

Comments are closed.